Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences

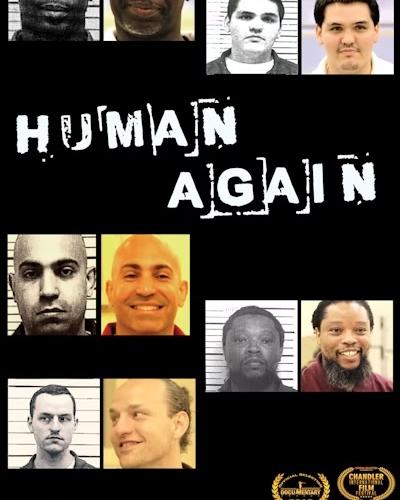

Discovering and exposing a treasure trove of film history

When Samantha Sheppard, assistant professor in the Department of Performing and Media Arts, contemplated the movies she would include in a fall film and speaker series on Black cinema, she had a tough time choosing only five.